|

|

Search Colesberg

Accommodation

The history of Colesberg

You might find yourself booking some more accommodation nights in an aim to experience more of the Colesberg's rich history.

Colesberg was named after Sir Lowry Cole – governor of the Cape of Good Hope 1828 – 1833.

The first people to inhabit the Colesberg district were stone-age hunter-gatherers. They were followed in the early 19th century by ‘trekboere’, migrant farmers and missionaries.

By 1814, a mission station had been established in the hopes of bringing peace to what was an extremely unruly frontier area of the Cape Colony.

Soon a second mission station, called Hepzibah, was established nearby and within short the two stations attracted over 1 700 /Xam San (Bushmen). This caused great alarm among frontier settlers who felt their security was threatened. They appealed to the Governor to assure their safety, but there was little improvement and in 1818 the Cape Colonial Government stepped in and put an end to the mission work.

By 1820 several huge farms had been established in the district and in 1822 the farmers petitioned for the establishment of a town. The Government granted 18 138 morgen of land to the Dutch Reformed Church on January 27, 1830, and so Colesberg, named after Sir Lowry Cole, (Governor from 1828 to 1833), was established.

For many years it remained one of the most remote outposts of European settlement at the Cape and, as a result, became a major base for commercial hunters, explorers and settlers travelling into the southern African interior.

The district of Colesberg was proclaimed on 8 February 1837. It became a municipality in 1840. Over the next 52 years various portions of its territory were separated to form new divisions at Albert and Richmond in 1848, Middelburg in 1858, Hanover in 1876, and Philipstown and Steynsburg in 1889.

The settlement was laid out about a central axis dominated by the Dutch Reformed church, and its dwellings were distinctive for their square, flat-roofed construction, a form of residential architecture which eventually became ubiquitous in the central, more arid regions of the Cape. Residents were served by the The Colesberg Advertiser, a bilingual weekly newspaper established locally in 1861.

The division lies on an elevated plateau studded with flat-topped koppies which, in pre-colonial times, was the habitat of vast herds of buck. The region suffered from a dearth of natural timber but its extensive plains were suited for sheep farming.

Colesberg’s part in the Anglo-Boer War

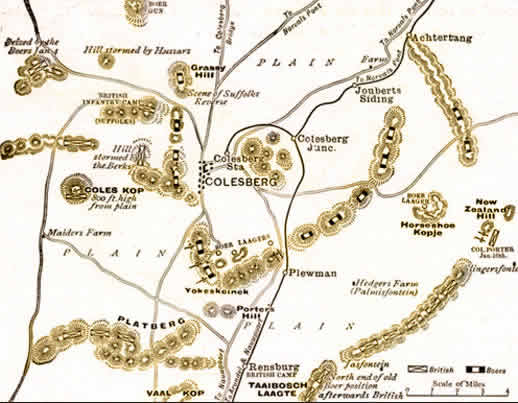

- On 14 November 1899 a Boer force of 700 men under the joint command of Chief Comdt ER Grobler and General HJ Schoeman entered Colesberg unopposed.

- On 1 January 1900 British troops under Maj-Gen John French attacked Boer forces in and around Colesberg.

- On 11 January they managed to drag a 15-pounder Armstrong gun to the top of Coleskop, overlooking the town, and on the next day they began shelling the town.

- On 14 February the British withdrew from their positions around Colesberg and regrouped at Arundel Siding.

- On 20 February the Boers began to retreat from Colesberg, and on 28 February British forces under Maj-Gen RAP Clements marched into the town unopposed.

- The railway line to Colesberg Junction was reopened on 2 March 1900.

- However Boer forces continued to control the Orange Free State banks of the Gariep and on 2 March 1900 they dynamited the Colesberg road bridge.

- They finally retreated from the area on 7 March 1900.

THE MAGIC MOUNTAIN

The town lies in typical Karoo veld and is surrounded by koppies (little hills). The most famous is Coleskop, which can be seen from a distance of over 40km. Early travellers called it “Towerberg” (“Magic Mountain”). The curious thing about this koppie is that as you travel towards it, it never seems to get nearer. At the foot of this mountain was a marsh where travelers watered their animals, and game also frequented the hole.

Colesberg has a rich history closely linked with to the legendary characters of South Africa’s diamond industry.

John O’Reiley, who purchased the first diamond found in South Africa from its owner, Schalk van Niekerk, took it to Colesberg for testing. It was used to scratch “DP”, the initials of Draper and Plewman, a store which still exists, on the shop’s window. Once the stone passed this test, it was sent to Dr Guybourne Atherstone, a well-known geologist. He confirmed it was a diamond and so started “The Diamond Rush”.

CENCUS:

The following census figures are available for the division:

1841 census: 9,026 residents

1865 census: 8,115 residents, of whom 2,127 were literate

1875 census: 10,368 residents, of whom 2,798 were literate

1891 census: 8,288 residents, of whom 2,574 were literate

1904 census: 11,716 residents, of whom 4,496 were literate

Credits - Lots of thanks to Belinda Gordon for information she provided for this site.

The Van Rensburg’s of Rensburg Siding, Colesberg, Cape

During the Anglo-Boer War 1899 – 1902 16,000 Australians served with official contingents, and another 8,000 joined irregular South African units. The first Australian casualties were suffered near the town of Colesberg, at a desolate stopping place for trains, called Rensburg Siding. The siding was obviously named after members of a Van Rensburg family who have until now not been identified by historians. An endeavour shall now be made to explore their background and to give a factual account of the various skirmishes which took place at Renburg Siding, Arundel, Australian Hill, New Zealand Hill, Slingerfontein and places around Colesberg.

To start we need to go back a generation. Nicolaas Albertus Jansen van Rensburg was married in Mosselbaai in 1850 to Margaretha Isabella Rautenbach (daughter of Georg Frederik Rautenbach and Elsje Catharina Roelofse). He was from the farm Rietfontein in the Colesberg district and she was from the farm Brakfontein, near Mosselbaai. Nicloaas and Margaretha’s membership of the Dutch Reformed Church were transferred to Colesberg from Mosselbaai on 10 August 1878, most likely to join some of the children who moved there earlier.

They had the following children:

g1 Nicolaas Albertus baptised on 21 December 1851 at Mosselbaai, married Margaretha Adriana van Schalkwyk

g2 Elsje Catharina born 2 Apr 1853, baptised 15 May 1853, married 10 Jan 1870 Petrus Jacobus Venter (In 1883 he was living on the farm Vaalkop)

g3 George Frederik (Frikkie) baptised 9 Dec 1855, became a member at Colesberg 9 Aug 1875. He married 21 Apr 1890 Amerentia Margaretha du Preez, married again Magdalena Johanna Swanepoel

g4 Hester Catharina Susanna baptised 10 Jan 1858. She became a church member at Colesberg on 4 Aug 1873. She married at Colesberg, Izak Jacobus de Villiers, remarried Oct 1886 Johan Frederik Botha (according to their childrens baptismal entries they lived on the farm Vaalkop in 1887 and 1889)

g5 Louisa Jacobus baptised 12 Feb 1860

g6 Johannes Andries,

married Catharine Ann (Katie) Goedhals

g7 Margaretha Isabella (Grieta) baptised 15 May 1864, married 16 Feb 1891 Jacobus Philippus Bezuidenhout

g8 Dirk de Wet

g9 Louis Josephus born 16 Sept 1867, baptised 24 Nov 1867, married Adriana Josine Meyer (witnesses at his baptism included: Louis Jacobus Janse van Rensburg, Susanna Lamberta Zaayman, Josefus Rudolphus Janse van Rensburg, Susanna Fourie)

g 10 Cornelis Johannes (John) born 31 May 1870, baptised Colesberg 18 Sept 1870, married Hester Cornelia de Plessis (witnesses at his baptism included: Petrus Venter, Eljse Catharina Janse van Rensburg, Cornelis Johannes Janse van Rensburg, Louisa Janse van Rensburg)

Three of these sons and their farms featured in the Anglo-Boer War. Amazingly two of the farms were the headquarters for the English and Boer forces, and one of these farms were the headquarters for both sides at different times.

The eldest son was born on 5 August 1851 and they also named him Nicolaas Albertus Jansen van Rensburg (b1 c1 d6 e1 f2 g1). This child was baptised on 21 December 1851 at Mosselbaai. The family trekked some time after 1855 and settled at the farm Taaiboslaagte, Colesberg. This is also further confirmed in personal correspondence with Jean G le Roux, who states that no Van Rensburgs owned any farms in the Colesberg area before 1855. The father passed away 24 July 1897 and the mother died 15 August 1915.

The son Nicolaas Albertus Jansen van Rensburg (b1 c1 d6 e1 f2 g1). He was accepted into Dutch Reformed church at Colesberg when he was 17 years on 8 February 1869. His sister Elsje Catharina also became a member on the same day. He got married at Philippolis on 7 April 1875 to Anna Margaretha Adriana van Schalkwyk. This couple lived on the farm Rietfontein, Arundel, a few kilometers south of Colesberg.

They had the following children:

h1 Anna Adriana Margaretha (Attie) born 8 April 1877, baptised 21 Jan 1878 Colesberg, married Colesberg 22 Jan 1901 Johannes Christian Rabie

h2 Margaretha Isabella born 20 Aug 1878, baptised Colesberg 1 Dec 1878, married 16 April 1902 James Charles Norval

h3 Esther Maria Violette born 30 May 1880 baptised Colesberg 1 Aug 1880 (witness George Frederik J v Rensburg), married 8 July 1903 Nicolaas Albertus Venter

h4 Nicholina Albertina born 14 Jan 1882, baptised Colesberg 5 March 1882, married Colesberg 22 Apr 1912 Charl Jacob du Plessis, married again Colesberg 4 Feb 1925 Ockert Jacobus Venter

h5 Nicolaas Albertus born 10 Oct 1884 baptised Colesberg 25 Jan 1884 (It is stated that his parents were from Taaiboschlaagte), married Rachel Susanna Elizabeth Henning

(During the ABW this boy was imprisoned when he was 16 years old. The English caught him at the local tennis court at Colesberg. They captured him because of a letter he wrote to his father, who was a Boer collaborator imprisoned at Tokai, Cape Town. The young Nicolaas was sent to Port Alfred as an ‘undesirable’.

h6 Maria Monica born 20 Apr 1892, baptised Colesberg 5 Jun 1892 (Parents from Rietfontein) witnesses included: George Fredrik Janse van Rensburg, Emarensia Janse van Rensburg, Johan Janse van Rensburg, Gertruida Maria de Villiers.

The son Johannes Andries van Rensburg (b1 c1 d6 e1 f2 g6) got married to Catharine Ann Goedhals. The farm Vaalkop belonged to him.

Some of their children were:

Jessie Cameron born 15 Aug 1908, baptised Colesberg 25 Sept 1908 (witnesses included Cornelis Janse van Rensburg and Hester Cornelia Janse van Rensburg). At the time of the baptism the family lived on the farm Vaalkop.

Margaretha Isabella Rautenbach born 8 Feb 1910, baptised Colesberg 1 May 1910 (witnesses included Anna Catherina Goedhals, Nicolaas Albertus Janse van Rensburg, Violet van Rensburg

The other son Cornelis Johannes (John) van Rensburg (b1 c1 d6 e1 f2 g10) who was born 31 May 1870 and baptised at Colesberg 19 September 1870. He got married to Hester Cornelia du Plessis and they lived on the farmTaaiboslaagte(today known as Hugoslaagte). Rensburg Siding was on this farm. The railway line between Colesberg and Rosmead were opened on 17th December 1890. John van Rensburg was a so called “Rebel” according to the Cape Times.

Some of their children were:

Anna Catharina born 7 Aug 1903, baptised 20 Sept 1903 (witnesses included Esther Maria Violetta Janse van Rensburg, Nicolaas Albertus Venter)

Johanna Albertus born 28 Sept 1906, baptised 2 Dec 1906 (witnesses included Johan Andries Janse van Rensburg)

Petrus du Plessis born 31 Dec 1907, baptised 17 Feb 1908

At the start of the Anglo-Boer War, Boer forces from the two Republics invaded the northern parts of the Cape and occupied the area. Colesberg was captured 13 November 1899 under the leadership of General Hendrik Jacobus Schoeman (11 Jul 1840 – 26 May 1901) and Commandant Esias Reinier Grobler (3 Jan 1861 – 31 Aug 1937). The arrival of the Boers received a lot of local support, and a number of local burghers joined the commandos. On 14 November 1899 a committee of six local members were elected to assist the Boer commandos with provisions, and what ever else they needed. One of these members were Nicolaas Albertus Janse van Rensburg, who lived at Rietfontein, Arundel. He was a very well known and very influential burgher in the area.

General French used the tactic of giving the impression that his forces were much larger than they really were. The Boers thus did not take the initiative with attacking.

During the Anglo-Boer War the British wanted to take control of Naauwpoort. It was a strategic position, since the railway junction from Cape Town, Port Elizabeth and Bloemfontein was situated here. A few miles north was Arundel. Ten miles north of Arundel was Rensburg Siding. Ten miles north of Rensburg Siding is the town Colesberg,see map. During the Anglo-Boer War Australians and New Zealanders served here, and a number of them were killed in battles in this area. As there was not one big battle, rather many smaller battles, the account of the Anglo-Boer war around Colesberg has not been emphasised as much.

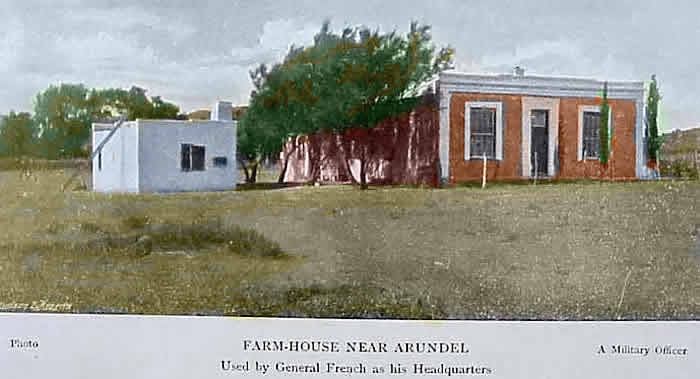

The British forces advanced under the command of General John DP French to Naauwpoort. On 21 November French and his soldiers entered Arundel and found it empty. French then went to the farm Rietfontein, which belonged to Nicolaas Albertus Janse van Rensburg, and captured Nicolaas Albertus Janse van Rensburg at the water canal. He was given very little time to say good bye to his family. The British took him and left his wife and two daughters destitute. Van Rensburg had to ride with his horse, accompanied by four British soldiers on horses, one at the front and one at the rear, and one on each side. They rode south and once they reachedTweedale he was transported further by train. Apparently Van Rensburg was one of the very first Boers to be arrested in the Colesberg area.

General French made his headquarters at Arundel, and on 17 December 1899 he moved into the Rietfontein farmhouse belonging to Nicolaas Albertus van Rensburg.It is not known wat happened to the homestead’s furniture at the time of the occupation.

The house of Nicolaas Albertus Jansen van Rensburg and Margaretha Adriana van Schalkwyk on their farm Rietfontein, Arundel

General John DP French made this his headquarters

During all these happenings the Boers were still based at Rensburg Siding on the other brother, John van Rensburg’s farm, Taaiboslaagte.

On 29 December 1899 General Schoeman abandoned Rensburg Siding and retreated to Colesberg.

The next day 30 December 1899, General French occupied the home of Cornelis Johannes (John) van Rensburg and Hester Cornelia du Plessis at Rensburg Siding, and used it as his headquarters. To the dismay of the owners he stayed there for some time.We should not forget that Rensburg Siding was on the farm Taaiboslaagte (today it is called Hugoslaagte).

As the Boers succesfully attacked the English on 12 February 1900, the English soldiers were forced to retreat back to Rensburg Siding.Early on February 13th, General De la Rey attacked the headquarters at Rensburg Siding, while on the 14th February R.A.P. Clements withdrew to the nearby Arundel. The Boers thus captured Rensburg Siding.

E J Murray wrote in his report entitled; “At The Front – and how we spent New Year” (Written at the top of Coleskop):

“More or less since about the 8th of December we have been continually having skirmishes with the enemy. General French, (a very cautious General), keeps on harassing them on all sides with artillery. For reasons unknown to us the enemy have evacuated their position at Arundel, and Colonel Porter, of the Carabiniers, went to reconnoitre. He found them on the kopjes outside Plewman siding. I was mounted with a telegraph instrument and remained at Rensburg farmhouse. eing alone, more or less, the Rensburg farmer being a rebel and having cleared with the Dutch, I turned my attention to his poultry yard, where I commandeered four geese, two hens and two dozen eggs. We had the two hens for dinner that night when the rest of our fellows arrived. I gave away two geese and told the receivers to ask no questions.”

From a diary written in Colesberg in December 1899 (Held at Colesberg Museum and information supplied by Belinda Gordon):

“The grim side of the war can be seen by visiting the Church Hall Temporary Hospital where men with bandaged heads and limbs are being nursed, said to be suffering from the measles. After the skirmish on Wednesday Mrs Tuiskop? [the wife of Cornelis Johannes van Rensburg] of Taaiboschlaagte received so many wounded Boers into her house that she could not find beds for them all & sent to the Government School boarding dept. for a doz whole beds. The hills E & W of Colesberg are lined with Boers & a special force of 600 is kept at the junction ready to proceed at a moments notice to any point threatened. The artillery fire around Arundel can be distinctly heard in Colesberg”.

General French and his staff 30 December 1900

after the Boers retreated from RensburgSiding

A photo of General French

Nicolaas Albertus Janse van Rensburg spent the whole of 1900 in the police jail at Colesberg. Fortunately for him, he was allowed to receive visits from his wife and children. During March 1900 a number of other people got arrested and they were put in the same prison cell with him, Ds GA Scholtz and his son Dicke, Herman Sluiter (not the lawyer), Tobias de Villiers, P Badenhorst, Jacobus Pienaar, F Jooste Isak van Zyl, Arnoldus Meiring, Jacobus Norval, Charl Norval. In the cold winter months the freezing conditions made life very misearble in the cells. In the cell they hardly received any exercise and the food was meager.

On 10 December 1899 Van Rensburg received a visit from General Fouché, who informed him told that the English were in possession of Arundel. He then asked van Rensburg whether he could use some of his rooms at the farmhouse. Van Rensburg had no objections to this request and gave his permission accordingly.

The next day Van Rensburg was informed by Captain Kenna that his farm was broken in and that all the furniture had been destroyed. Van Rensburg also had 300 pounds in the house and found that the money mysteriously disappeared. The following day the English wanted to buy sheep, and Van Rensburg agreed to sell it at 25 shillings each. The English said that the price was to high and reduced it by half. They took the sheep, with the promise of paying later, however he never received the money from them. Shortly afterwards 65 of his cattle were stolen by the English troops from the nearby Naauwpoort.

Who was Kenna?

“Paul Aloysius Kenna (Oakfield. Lanc 16.08.1862 – Suvia, Gallipoli 30.08.1915). He served with the 2nd West India Regt. In 1889 he transferred to the 21st Hussars (later Lancers). During the Anglo-Boer war he served as Asst. Provost Marshal on General French’s staff. He then served as a brigade major and in 1901 commanded a column. Kenna then commanded the Mounted Troops during the Somaliland Campaign and was promoted lieutenant-colonel. Kenna was an outstanding polo player. In 1905 he became a colonel and ADC to the King. In August 1914 Kenna was promoted brigadier general in the Notts and Derby Regiment. At Gallipoli, while doing a tour in the front lines, he was shot by a sniper and mortally wounded. Brigadier General Kenna VC DSO is buried at Suvia Bay”. Ian Uys,South African Military Who’s who 1452 1992, p. 119.

On 5 December 1900 a special court was held in Colesberg (the presiding judge was Solomon). Seven days later, on the 12th December, Nicolaas Albertus Janse van Rensburg (already serving one year) was sentenced to serve three and half years in prison, and fined 500 pounds. On the 17 December he was told at 8am in the morning, to be ready to leave at 2pm that day. There was no time to greet his family. From the old Colesberg Station they were transported in open train trucks to the Junction. From there they were put in enclosed cattle trucks. At Naauwpoort they were placed on a passenger train to be taken to Cape Town. He arrived at Tokai prison on 22 December 1900, now one man amongst 628 other prisoners. Tokai was also a transit camp and some prisoners were sent to Bermuda or elsewhere. The brother Andries van Rensburg from the farmVaalkop (the farm is situated west of Rensburg Siding and Arundel), was also imprisoned at Tokai.(He was – g6 Johannes Andries)

At the end of the Anglo Boer War, signed at Vereeniging, 31 May 1902, John and Andries van Rensburg with many others were POW’s in Bermuda and India.Whereas Nicolaas Albertus Janse van Rensburg was still in the prison at Tokai. Nicolaas Albertus was only released six months after peace was declared — only to return to his farm destroyed by the English.

After the War NAJ van Rensburg received 3,000 pound war damages, but he claimed that his losses were 12,000 pounds.

Sources

A big thanks to Tannie Nelie van Rensburg from Colesberg who made her late husbands NAJ van Rensburg’s research available on request.

NAJ van Rensburg, Die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog in en om Colesberg (Unpublished paper byb1 c1 d6 e1 f2 g1 h5 i1 (deceased 1 March 1985) of his grandfather NAJ van Rensburg of the farm Rietfontein, Arundel). This author, N A J van Rensburg was an elder of the church at Colesberg when simultaneously he was the Chairman of the planning committee for the centenial anniversary of the Colesberg church in 1966, at which time they wrote and produced the book – Ons Kerk: Ned Geref Kerk Colesberg ingewy 1866. He was also a member of the building committee responsible for the renovations of the church and erection of the church tower, clock and weather cock. (See photo below where he is a member of the church council).

A big thanks to the assistance of Willem and Diana Loock from Platberg, Middelburg, Cape, South Africa who helped me obtain the primary information from Colesberg.

I also want to thank Anneli McClachlen (nee van Rensburg) living in Adelaide, she is a descendant of NAJ van Rensburg.

Special thanks to Mrs Belinda Gordon.

I want to thank Alwyn P Smit, the author ofGedenkboek van M.J. de Jager (1872 – 1939), Boerekryger, Staatsartilleris en militêr, in obtaining material dealing with the ABO at Colesberg and for his advise.

GJ Rautenbach, Van Rensburg family tree (unpublished paper, Jan 1992)

CN Robinson, With Roberts to the Transvaal, Part 2

Suid-Afrikaanse Geslagregister, Vol 9

Colesberg Dutch Reformed Church baptism and marriage records.

THE HISTORY OF ORTLEPP HOUSE

Ortlepp House, which celebrated its 160th birthday in 2004, is one of the town’s few historical buildings which has since been meticulously restored to its erstwhile Victorian splendour.

Typical of those rough and ready pioneering days,it is also the history of how the granddaughter of an itinerant local immigrant smouse ended up as the wife of a Randlord – by way of the diamond fields of Kimberley.

For, the most famous of Adolph Ortlepp`s descendants was indubitably Dorothea Sarah Florence Alexandra (Florrie) Ortlepp who later entered history as Lady Florence Philips, wife of diamond and Rand pioneer Sir Lionel Philips and as one of the original donors of the Johannesburg Art Gallery. Although born in Cape Town on June 14, 1863,

She was baptised in Colesberg by the rev Richard Giddy and also grew up here before her father, Albert Frederick (second son of Adolph Ortlepp) and his wife, Sarah Walker, moved to Kimberley during the diamond rush of 1869.

Her grandfather, Adolph Ortlepp, who was born in Silesia (Germany/Poland) in 1807, settled in Colesberg in 1836 as a missionary of the Berlin Missionary Society.

He acquired the double-stored Victorian trading store and dwelling house at 30 Church Street, later to become known as Ortlepp House, from traders PJ Hugh and W Fleming in December, 1849, and from where Ortelepp later also traded and bartered animal skins, horns, horses and weapons.

He died here in 1879 and was buried in the old cemetery across from the old Colesberg Hotel (now the Towerberg Hotel).

The original owners built and registered the house on September 1, 1844, on a site acquired ~from the Dutch Reformed church, only 14 years after Colesberg was proclaimed as a municipality.

The family’s historic homestead and trading store with its typical Victorian “broekies’~ lace wrought iron verendah was recently .’tensively restored and rnrves as prestigious business premises today.

Adolph married Dorothea Wilhelmine Florentienti Waldeck, the daughter of a local carpenter, at Colesberg in 1838.

His second son, Albert Frederick (born 1840) left for Kimberley when Florrie was nearly seven years old and her brother, Albert James, Just five.

Florrie subrnquently attended Miss Wilmot0s Select School for Ladies in Wynberg, Gape Town, before returning to Kiuiberley where she later met her future husband, Lionel Philipe at a picnic in 1883.

They were married two years later, afterwards living mainly in Johannesburg and London and Somerrnt West where Lady Philips lovingly restored the farshoum at Vergelegen Somerrnt West), originally owned by Willem Adriaan van der Stel, son of Gape Governor Simon van der Stel.

She died here on August 22, 1940, but is buried with her husband and eldest son, Harold, in Brixton, Johannesburg.

RACE HORSES

| Scot by birth, Alex Robertson was a trainer, owner and breeder who married into an old Cape family. Five early South African Derby winners — Irene, Lammas, Diana, Blanche and Colesberg — were bred by Robertson, whose stud, Stormfontein, was located near Colesberg. He also bred a top South African sprinter, Abelard, and co-owned the 1895 South African Derby winner Rosary. He imported the stallion Uniform, from New Zealand, who sired Derby winner Diana, and then, in 1911, the unracedSt. Simonson, Simontault, who had been injured as a yearling, in 1911, but the stallion died early, in 1916, although not before he had gotten Blanche and some other good runners for Stormfontein.Colesberg (1917), who was by the imported British horse Wilfred, and out of a Uniform daughter, was sold by Robertson as a yearling for 150 guineas; in addition to winning the Derby, he won the Guineas and the St. Leger at Benoni, becoming South Africa’s first “triple crown” winner.

Robertson’s son, Allan, continued from his father and became an authority in racehorse breeding and administration. During the Boer War (1899-1902), the then ten year old Allan and his mother managed the stud whilst Alex was away on active service, and were forced to watch a Boer commando unit appropriate four stallions and thirty mares, all of which were returned the following day by a Boer general who had been informed that some of the horses belonged to wealthy Randlord Abe Bailey.Stormfontein-bred horses ran successfully well into the 20th Century. Stormfontein’s principal stallion in the late ’20s and early ’30s, Kerasos (by Kennymore, aJohn o’ Gaunt son), was champion sire in 1935. |

| After World War II, Robertson imported the well-bred Mehrali (Mahmoud – Una, and a half-brother to Palestine), who was the grandsire of Hawaii. He also imported the highly successful Abadan, who stood for one season in Ireland before coming to South Africa. His crop there included the Irish 2000 Guineas winner Jack Ketch (later a sire in Australia) and My Pal, later a good sire in New Zealand. In South Africa, Abadan was leading sire in 1960; he was later repatriated to Engla |

Hawaii

(1964, by Utrillo) was bred by A.L. Dell at his Platberg Stud in Colesberg, where the Italian-bred Utrillo stood; his dam, Ethane, was a second generation South African-bred mare and an excellent producer of eleven winners of over 50 races. Purchased by New Jersey millionaire Charles Engelhard when a yearling for $12,642, Hawaii ‘s wins of fifteen races in South Africa made him the country’s champion racehorse, after which, in late 1968, Engelhard sent him to the U.S. to run , where he won six good races (five on the turf), including the the United Nations and Sunrise handicaps at Atlantic City, and the Man o’ War handicap at Belmont, where he set a new track record for 1-1/2 miles. He did not return to South Africa, instead syndicated for 1.12 million dollars and sent to Claiborne Farm, Kentucky, to stand at stud; one of his sons, Henbit, won the 1980 Epsom Derby.

Wrote the book: The Microcosm - Gutsche (Thelma) THE MICROCOSM, An acclaimed 19th Century history of Colesberg and district, and of thre Diamond Fields |

(Sources: E.J. Verwey (ed), New dictionary of South African biography. Pretoria, 1995, pp 88-89

|

The Colesberg Operations

Of the four British armies in the field I have attempted to tell the story of the western one which advanced to help Kimberley, of the eastern one which was repulsed at Colenso, and of the central one which was checked at Stormberg. There remains one other central one, some account of which must now be given.

It was, as has already been pointed out, a long three weeks after the declaration of war before the forces of the Orange Free State began to invade Cape Colony. But for this most providential delay it is probable that the ultimate fighting would have been, not among the mountains and kopjes of Stormberg and Colesberg, but amid those formidable passes which lie in the Hex Valley, immediately to the north of Cape Town, and that the armies of the invader would have been doubled by their kinsmen of the Colony. The ultimate result of the war must have been the same, but the sight of all South Africa in flames might have brought about those Continental complications which have always been so grave a menace.

The invasion of the Colony was at two points along the line of the two railways which connect the countries, the one passing over the Orange River at Norval’s Pont and the other at Bethulie, about forty miles to the eastward. There were no British troops available (a fact to be considered by those, if any remain, who imagine that the British entertained any design against the Republics), and the Boers jogged slowly southward amid a Dutch population who hesitated between their unity of race and speech and their knowledge of just and generous treatment by the Empire. A large number were won over by the invaders, and, like all apostates, distinguished themselves by their virulence and harshness towards their loyal neighbours. Here and there in towns which were off the railway line, in Barkly East or Ladygrey, the farmers met together with rifle and bandolier, tied orange puggarees round their hats, and rode off to join the enemy. Possibly these ignorant and isolated men hardly recognised what it was that they were doing. They have found out since. In some of the border districts the rebels numbered ninety per cent of the Dutch population.

In the meanwhile, the British leaders had been strenuously endeavouring to scrape together a few troops with which to make some stand against the enemy. For this purpose two small forces were necessary – the one to oppose the advance through Bethulie and Stormberg, the other to meet the invaders, who, having passed the river at Norval’s Pont, had now occupied Colesberg. The former task was, as already shown, committed to General Gatacre. The latter was allotted to General French, the victor of Elandslaagte, who had escaped in the very last train from Ladysmith, and had taken over this new and important duty. French’s force assembled at Arundel and Gatacre’s at Sterkstroom. It is with the operations of the former that we have now to deal.

General French, for whom South Africa has for once proved not the grave but the cradle of a reputation, had before the war gained some name as a smart and energetic cavalry officer. There were some who, watching his handling of a considerable body of horse at the great Salisbury manoeuvres in 1898, conceived the highest opinion of his capacity, and it was due to the strong support of General Buller, who had commanded in these peaceful operations, that French received his appointment for South Africa. In person he is short and thick, with a pugnacious jaw. In character he is a man of cold persistence and of fiery energy, cautious and yet audacious, weighing his actions well, but carrying them out with the dash which befits a mounted leader. He is remarkable for the quickness of his decision – ‘can think at a gallop,’ as an admirer expressed it. Such was the man, alert, resourceful, and determined, to whom was entrusted the holding back of the Colesberg Boers.

Although the main advance of the invaders was along the lines of the two railways, they ventured, as they realised how weak the forces were which opposed them, to break off both to the east and west, occupying Dordrecht on one side and Steynsberg on the other. Nothing of importance accrued from the possession of these points, and our attention may be concentrated upon the main line of action.

French’s original force was a mere handful of men, scraped together from anywhere. Naauwpoort was his base, and thence he made a reconnaissance by rail on November 23rd towards Arundel, the next hamlet along the line, taking with him a company of the Black Watch, forty mounted infantry, and a troop of the New South Wales Lancers. Nothing resulted from the expedition save that the two forces came into touch with each other, a touch which was sustained for months under many vicissitudes, until the invaders were driven back once more over Norval’s Pont. Finding that Arundel was weakly held, French advanced up to it, and established his camp there towards the end of December, within six miles of the Boer lines at Rensburg, to the south of Colesberg. His mission – with his present forces – was to prevent the further advance of the enemy into the Colony, but he was not strong enough yet to make a serious attempt to drive them out.

Before the move to Arundel on December 13th his detachment had increased in size, and consisted largely of mounted men, so that it attained a mobility very unusual for a British force. On December 13th there was an attempt upon the part of the Boers to advance south, which was easily held by the British Cavalry and Horse Artillery. The country over which French was operating is dotted with those singular kopjes which the Boer loves – kopjes which are often so grotesque in shape that one feels as if they must be due to some error of refraction when one looks at them. But, on the other hand, between these hills there lie wide stretches of the green or russet savanna, the noblest field that a horseman or a horse gunner could wish. The riflemen clung to the hills, French’s troopers circled warily upon the plain, gradually contracting the Boer position by threatening to cut off this or that outlying kopje, and so the enemy was slowly herded into Colesberg. The small but mobile British force covered a very large area, and hardly a day passed that one or other part of it did not come in contact with the enemy. With one regiment of infantry (the Berkshires) to hold the centre, his hard-riding Tasmanians, New-Zealanders, and Australians, with the Scots Greys, the Inniskillings, and the Carabineers, formed an elastic but impenetrable screen to cover the Colony. They were aided by two batteries, 0 and R, of Horse Artillery. Every day General French rode out and made a close personal examination of the enemy’s position, while his scouts and outposts were instructed to maintain the closest possible touch.

On December 30th the enemy abandoned Rensburg, which had been their advanced post, and concentrated at Colesberg, upon which French moved his force up and seized Rensburg. The very next day, December 31st, he began a vigorous and long-continued series of operations. At five o’clock on Sunday evening he moved out of Rensburg camp, with R and half of 0 batteries R.H.A., the 10th Hussars, the Inniskillings, and the Berkshires, to take up a position on the west of Colesberg. At the same time Colonel Porter, with the half-battery of 0, his own regiment (the Carabineers), and the New Zealand Mounted Rifles, left camp at two on the Monday morning and took a position on the enemy’s left flank. The Berkshires under Major McCracken seized hill, driving a Boer picket off it, and the Horse enfiladed the enemy’s right flank, and after a risk artillery duel succeeded in silencing his guns. Next morning, however (January 2nd, 1900), it was found that the Boers, strongly reinforced, were back near their old positions, and French had to be content to hold them and to wait for more troops.

These were not long in coming, for the Suffolk Regiment had arrived, followed by the Composite Regiment (chosen from the Household Cavalry) and the 4th Battery R.F.A. The Boers, however, had also been reinforced, and showed great energy in their effort to break the cordon which was being drawn round them. Upon the 4th a determined effort was made by about a thousand of them under General Shoemann to turn the left flank of the British, and at dawn it was actually found that they had eluded the vigilance of the outposts and had established themselves upon a hill to the rear of the position. They were shelled off of it, however, by the guns of 0 Battery, and in their retreat across the plain they were pursued by the 10th Hussars and by one squadron of the Inniskillings, who cut off some of the fugitives. At the same time, De Lisle with his mounted infantry carried the position which they had originally held. In this successful and well-managed action the Boer loss was ninety, and we took in addition twenty-one prisoners. Our own casualties amounted only to six killed, including Major Harvey of the 10th, and to fifteen wounded.

Encouraged by this success an attempt was made by the Suffolk Regiment to carry a hill which formed the key of the enemy’s position. The town of Colesberg lies in a basin surrounded by a ring of kopjes, and the possession by us of any one of them would have made the place untenable. The plan has been ascribed to Colonel Watson of the Suffolks, but it is time that some protest should be raised against this devolution of responsibility upon subordinates in the event of failure. When success has crowned our arms we have been delighted to honour our general; but when our efforts end in failure our attention is called to Colonel Watson, Colonel Long, or Colonel Thorneycroft. It is fairer to state that in this instance General French ordered Colonel Watson to make a night attack upon the hill.

The result was disastrous. At midnight four companies in canvas shoes or in their stocking feet set forth upon their venture, and just before dawn they found themselves upon the slope of the hill. They were in a formation of quarter column with files extended to two paces; H Company was leading. When half-way up a warm fire was opened upon them in the darkness. Colonel Watson gave the order to retire, intending, as it is believed, that the men should get under the shelter of the dead ground which they had just quitted, but his death immediately afterwards left matters in a confused condition. The night was black, the ground broken, a hail of bullets whizzing through the ranks. Companies got mixed in the darkness and contradictory orders were issued. The leading company held its ground, though each of the officers, Brett, Carey, and Butler, was struck down. The other companies had retired, however, and the dawn found this fringe of men, most of them wounded, lying under the very rifles of the Boers. Even then they held out for some time, but they could neither advance, retire, or stay where they were without losing lives to no purpose, so the survivors were compelled to surrender. There is better evidence here than at Magersfontein that the enemy were warned and ready. Every one of the officers engaged, from the Colonel to the boy subaltern, was killed, wounded, or taken. Eleven officers and one hundred and fifty men were our losses in this unfortunate but not discreditable affair, which proves once more how much accuracy and how much secrecy is necessary for a successful night attack. Four companies of the regiment were sent down to Port Elizabeth to re-officer, but the arrival of the 1st Essex enabled French to fill the gap which had been made in his force.

In spite of this annoying check, French continued to pursue his original design of holding the enemy in front and working round him on the east. On January 9th, Porter, of the Carabineers, with his own regiment, two squadrons of Household Cavalry, the New-Zealanders, the New South Wales Lancers, and four guns, took another step forward and, after a skirmish, occupied a position called Slingersfontein, still further to the north and east, so as to menace the main road of retreat to Norval’s Pont. Some skirmishing followed, but the position was maintained. On the 15th the Boers, thinking that this long extension must have weakened us, made a spirited attack upon a position held by New-Zealanders and a company of the 1st Yorkshires, this regiment having been sent up to reinforce French. The attempt was met by a volley and a bayonet charge. Captain Orr, of the Yorkshires, was struck down; but Captain Madocks, of the New-Zealanders, who behaved with conspicuous gallantry at a critical instant, took command, and the enemy was heavily repulsed. Madocks engaged in a point-blank rifle duel with the frock-coated top-hatted Boer leader, and had the good fortune to kill his formidable opponent. Twenty-one Boer dead and many wounded left upon the field made a small set-off to the disaster of the Suffolks.

The next day, however (January 16th), the scales of fortune, which swung alternately one way and the other, were again tipped against us. It is difficult to give an intelligible account of the details of these operations, because they were carried out by thin fringes of men covering on both sides a very large area, each kopje occupied as a fort, and the intervening plains patrolled by cavalry.

As French extended to the east and north the Boers extended also to prevent him from outflanking them, and so the little armies stretched and stretched until they were two long mobile skirmishing lines. The actions therefore resolve themselves into the encounters of small bodies and the snapping up of exposed patrols – a game in which the Boer aptitude for guerrilla tactics gave them some advantage, though our own cavalry quickly adapted themselves to the new conditions. On this occasion a patrol of sixteen men from the South Australian Horse and New South Wales Lancers fell into an ambush, and eleven were captured. Of the remainder, three made their way back to camp, while one was killed and one was wounded.

The duel between French on the one side and Schoeman and Lambert on the other was from this onwards one of maneuvering rather than of fighting. The dangerously extended line of the British at this period, over thirty miles long, was reinforced, as has been mentioned, by the 1st Yorkshire and later by the 2nd Wiltshire and a section of the 37th Howitzer Battery. There was probably no very great difference in numbers between the two little armies, but the Boers now, as always, were working upon internal lines. The monotony of the operations was broken by the remarkable feat of the Essex Regiment, which succeeded by hawsers and good-will in getting two 15-pounder guns of the 4th Field Battery on to the top of Coleskop, a hill which rises several hundred feet from the plain and is so precipitous that it is no small task for an unhampered man to climb it. From the summit a fire, which for some days could not be localised by the Boers, was opened upon their laagers, which had to be shifted in consequence. This energetic action upon the part of our gunners may be set off against those other examples where commanders of batteries have shown that they had not yet appreciated what strong tackle and stout arms can accomplish. The guns upon Coleskop not only dominated all the smaller kopjes for a range of 9,000 yards, but completely commanded the town of Colesberg, which could not however, for humanitarian and political reasons, be shelled.

By gradual reinforcements the force under French had by the end of January attained the respectable figure of ten thousand men, strung over a large extent of country. His infantry consisted of the 2nd Berkshires, 1st Royal Irish, 2nd Wiltshires, 2nd Worcesters, 1st Essex, and 1st Yorkshires; his cavalry, of the 10th Hussars, the 6th Dragoon Guards, the Inniskillings, the New-Zealanders, the N.S.W. Lancers, some Rimington Guides, and the composite Household Regiment; his artillery, the R and 0 batteries of R.H.A., the 4th R.F.A., and a section of the 37th Howitzer Battery. At the risk of tedium I have repeated the units of this force, because there are no operations during the war, with the exception perhaps of those of the Rhodesian Column, concerning which it is so difficult to get a clear impression. The fluctuating forces, the vast range of country covered, and the petty farms which give their names to positions, all tend to make the issue vague and the narrative obscure. The British still lay in a semicircle extending from Slingersfontein upon the right to Kloof Camp upon the left, and the general scheme of operations continued to be an enveloping movement upon the right. General Clements commanded this section of the forces, while the energetic Porter carried out the successive advances. The lines had gradually stretched until they were nearly fifty miles in length, and something of the obscurity in which the operations have been left is due to the impossibility of any single correspondent having a clear idea of what was occurring over so extended a front.

On January 25th French sent Stephenson and Brabazon to push a reconnaissance to the north of Colesberg, and found that the Boers were making a fresh position at Rietfontein, nine miles nearer their own border. A small action ensued, in which we lost ten or twelve of the Wiltshire Regiment, and gained some knowledge of the enemy’s dispositions. For the remainder of the month the two forces remained in a state of equilibrium, each keenly on its guard, and neither strong enough to penetrate the lines of the other. General French descended to Cape Town to aid General Roberts in the elaboration of that plan which was soon to change the whole military situation in South Africa.

Reinforcements were still dribbling into the British force, Hoad’s Australian Regiment, which had been changed from infantry to cavalry, and J battery R.H.A. from India, being the last arrivals. But very much stronger reinforcements had arrived for the Boers – so strong that they were able to take the offensive. De la Rey had left the Modder with three thousand men, and their presence infused new life into the defenders of Colesberg. At the moment, too, that the Modder Boers were coming to Colesberg, the British had begun to send cavalry reinforcements to the Modder in preparation for the march to Kimberley, so that Clements’s Force (as it had now become) was depleted at the very instant when that of the enemy was largely increased. The result was that it was all they could do not merely to hold their own, but to avoid a very serious disaster.

The movements of De la Rey were directed towards turning the right of the position. On February 9th and 10th the mounted patrols, principally the Tasmanians, the Australians, and the Inniskillings, came in contact with the Boers, and some skirmishing ensued, with no heavy loss upon either side. A British patrol was surrounded and lost eleven prisoners, Tasmanians and Guides. On the 12th the Boer turning movement developed itself, and our position on the right at Slingersfontein was strongly attacked.

The key of the British position at this point was a kopje held by three companies of the 2nd Worcester Regiment. Upon this the Boers made a fierce onslaught, but were as fiercely repelled. They came up in the dark between the set of moon and rise of sun, as they had done at the great assault of Ladysmith, and the first dim light saw them in the advanced sangars. The Boer generals do not favour night attacks, but they are exceedingly fond of using darkness for taking up a good position and pushing onwards as soon as it is possible to see. This is what they did upon this occasion, and the first intimation which the outposts had of their presence was the rush of feet and loom of figures in the cold misty light of dawn. The occupants of the sangars were killed to a man, and the assailants rushed onwards. As the sun topped the line of the veldt half the kopje was in their possession. Shouting and firing, they pressed onwards.

But the Worcester men were steady old soldiers, and the battalion contained no less than four hundred and fifty marksmen in its ranks. Of these the companies upon the hill had their due proportion, and their fire was so accurate that the Boers found themselves unable to advance any further. Through the long day a desperate duel was maintained between the two lines of riflemen. Colonel Cuningham and Major Stubbs were killed while endeavouring to recover the ground which had been lost. Hovel and Bartholomew continued to encourage their men, and the British fire became so deadly that that of the Boers was dominated. Under the direction of Hacket Pain, who commanded the nearest post, guns of J battery were brought out into the open and shelled the portion of the kopje which was held by the Boers. The latter were reinforced, but could make no advance against the accurate rifle fire with which they were met. The Bisley champion of the battalion, with a bullet through his thigh, expended a hundred rounds before sinking from loss of blood. It was an excellent defence, and a pleasing exception to those too frequent cases where an isolated force has lost heart in face of a numerous and persistent foe. With the coming of darkness the Boers withdrew with a loss of over two hundred killed and wounded. Orders had come from Clements that the whole right wing should be drawn in, and in obedience to them the remains of the victorious companies were called in by Hacket Pain, who moved his force by night in the direction of Rensburg. The British loss in the action was twenty-eight killed and nearly a hundred wounded or missing, most of which was incurred when the sangars were rushed in the early morning.

While this action was fought upon the extreme right of the British position another as severe had occurred with much the same result upon the extreme left, where the 2nd Wiltshire Regiment was stationed. Some companies of this regiment were isolated upon a kopje and surrounded by the Boer riflemen when the pressure upon them was relieved by a desperate attack by about a hundred of the Victorian Rifles. The gallant Australians lost Major Eddy and six officers out of seven, with a large proportion of their men, but they proved once for a]l that amid all the scattered nations who came from the same home there is not one with a more fiery courage and a higher sense of martial duty than the men from the great island continent. It is the misfortune of the historian when dealing with these contingents that, as a rule, by their very nature they were employed in detached parties in fulfilling the duties which fall to the lot of scouts and light cavalry – duties which fill the casualty lists but not the pages of the chronicler. Be it said, however, once for all that throughout the whole African army there was nothing but the utmost admiration for the dash and spirit of the hard-riding, straight, shooting sons of Australia and New Zealand. In a host which held many brave men there were none braver than they.

It was evident from this time onwards that the turning movement had failed, and that the enemy had developed such strength that we were ourselves in imminent danger of being turned. The situation was a most serious one: for if Clements’s force could be brushed aside there would be nothing to keep the enemy from cutting the communications of the army which Roberts had assembled for his march into the Free State. Clements drew in his wings hurriedly and concentrated his whole force at Rensburg. It was a difficult operation in the face of an aggressive enemy, but the movements were well timed and admirably carried out. There is always the possibility of a retreat degenerating into a panic, and a panic at that moment would have been a most serious matter. One misfortune occurred, through which two companies of the Wiltshire regiment were left without definite orders, and were cut off and captured after a resistance in which a third of then number was killed and wounded. No man in that trying time worked harder than Colonel Carter of the Wiltshires (the night of the retreat was the sixth which he had spent without sleep), and the loss of the two companies is to be set down to one of those accidents which may always occur in warfare. Some of the Inniskilling Dragoons and Victorian Mounted Rifles were also cut off in the retreat, but on the whole Clements was very fortunate in being able to concentrate his scattered army with so few mishaps. The withdrawal was heartbreaking to the soldiers who had worked so hard and so long in extending the lines, but it might be regarded with equanimity by the Generals, who understood that the greater strength the enemy developed at Colesberg the less they would have to oppose the critical movements which were about to be carried out in the west. Meanwhile Coleskop had also been abandoned, the guns removed, and the whole force on February 14th passed through Rensburg and felt back upon Arundel, the spot from which six weeks earlier French had started upon this stirring series of operations. It would not be fair, however, to suppose that they had failed because they ended where they began. Their primary object had been to prevent the further advance of the Freestaters into the colony, and, during the most critical period of the war, this had been accomplished with much success and little loss. At last the pressure had become so severe that the enemy had to weaken the most essential part of their general position in order to relieve it. The object of the operations had really been attained when Clements found himself back at Arundel once more. French, the stormy petrel of the war, had flitted on from Cape Town to Modder River, where a larger prize than Colesberg awaited him. Clements continued to cover Naauwport, the important railway junction, until the advance of Roberts’s army caused a complete reversal of the whole military situation.

Instead of counting sheep in bed at your nice accommodation unit, think of how many people like you have slept between these same hills with their own challenges, plans and ideas. Yes they did not have most of the luxuries we had today, yet many of them where content with what they had.

Please note:

This history was compiled by numerous people and if you contributed to all this hard work without your name mentioned we apologise and kindly invite you to let us know so that we can give you the credit in this text. We thank everyone that worked so hard on this text and if you have something to add to this history page,

just contact us.

Use all information on this site at own risk. If you find information that needs to be updated, please contact us immediately.

Photos © 2014 by tourism photographer BerendPhotography.com / web & design by: eapproach.co.za